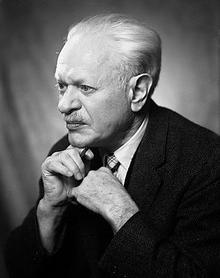

Kenneth Burke was a literary theorist, who had a powerful impact on 20th century criticism, rhetoric, and so forth. He analyzed the nature of knowledge and of language. Creative commons license.

As a starting basis, Burke believes that when we think, we use images, or symbols. More on that later. Burke believes that we have two main planes of thought: an absolute plane, where everything is absolute and set, and a conditional plane, where everything is fluid and there are no absolutes. What we do when we use figures of speech, then, is take these two planes and place them next to each other, connecting two ideas in a certain way to create a third new image, a completely separate idea. Burke claims (and no one after him has been able to disprove him) that all figures of speech can fit into four categories. These four categories are “metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony. And my primary concern with them here will not be with their purely figurative usage, but with their role in the discovery and description of ‘the truth’” (Grammar, 503). This “truth” that Burke speaks of is how we make sense of the world through language.

How do these four figures of speech deal with our two planes of thought? “For metaphor we could substitute perspective” (Grammar, 503). It’s when you take an object and substitute it for another object. It is a comparison between two things. “For metonymy we could substitute reduction” (Grammar, 503). This is when we make things bigger or smaller than they actually are. “For synecdoche we could substitute representation” (Grammar, 503). We take the part for the whole or the whole for the part. “For irony we could substitute dialectic” (Grammar, 503). Huh? It means that we see both planes at the same time, or we see two different perspectives simultaneously. You know, like an ironic joke where you understand both the joke meaning and the true meaning at the same time, and the combination of both at the same time is what makes it so ironic.

The idea of different planes of thoughts is important to figures of speech, but what about just regular thoughts, and regular communication? Well, Burke says “the antithetical relation between image and idea is replaced by a partial stress upon the bond of kinship between them.” (Rhetoric, 90). Wait, what? Basically, new ideas and thoughts come from taking old ideas and thoughts and making bridges or connections (bonds) between them. I have an idea about a tree. I have an idea about the concept of pink. When those two thoughts bond, they create this “kinship between them” which makes a new thought.

Burke argues that in order to understand or make sense of anything, we need to use symbols, or images. This is something that Aristotle agreed with. Burke also goes further and discusses that this connection of association between object and image symbol might be where abstract concepts came from. He says that “all abstractions themselves are necessarily expressed in terms of weakened and confused images, a consideration which doubtless explains why Aristotle said that we cannot think without images” (Rhetoric, 90). So, terms like “love” and “thought” and other abstract ideas got their beginning in the weakened state of confused images, or in the “kinship” in-between space where bonds are formed from connecting images and ideas together.

This in-between space where we make bonds of images together is where communication comes in. “You persuade a man only insofar as you can talk his language by speech, gesture, tonality, order, image, attitude, idea, identifying your ways with his” (Rhetoric 55). In order to communicate, you have to be on the same page, and in order to do that, you have to identify with your audience. In order to do that, you have to think the way they think. And how do you do that? This is where Burke’s ideas come together: you do so by thinking like them, which is by making the same sorts of connections between ideas as they would. If you create the same image-bonding that your audience would, then you are thinking the way they do, because that’s literally how you think: it’s connection pairs between ideas.

Wow. So suddenly Burke’s theory of language went from “I have no idea what’s going on” to “Holy Cow that explains how to connect with others and even explains how people think.” This is where the element of awe comes in, is realizing that if Burke is right then all human thought can be summed up in just a few rules. It’s also awesome how Burke is able to explain how abstract thought came to be.

All of these ideas all contribute to Juliet’s idea on how language evokes awe. Hopefully, with this new and unique way of looking at language, she’ll be able to find new insights in her topic and write one heck of a paper.

Works Cited

Burke, Kenneth. “A Grammar of Motives.” London: 1945. Print.

Burke, Kenneth. “A Rhetoric of Motives.” London: 1950. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment